In Drug Wars, former U.K. cop Neil Woods tells a story in which prohibition perpetuates corruption and addiction

The history of England's war on drugs recounts a decades-long series of missteps and unintended consequences that have ruined countless lives and failed to address demand for illicit narcotics

It can be difficult to imagine a world without the war on drugs.

A world without police officers knocking down doors or drawing their guns to seize a substance as relatively harmless as cannabis.

A world where there are no longer dealers peddling unknown products on street corners or using physical violence to settle their disputes with addicted customers.

A world in which people who struggle with an addiction receive compassionate care and treatment from the health-care system, instead of getting thrown into a prison cell for committing a crime that hurts no one but themselves.

In Drug Wars: The Terrifying Inside Story of Britain's Drug Trade, authors Neil Woods and JS Rafaeli remind us that we don't have to imagine this world. In fact, it was not so long ago that it was still the reality in the United Kingdom.

"There is a time in living memory for some people in the U.K. when there was no crime associated with drugs at all," Woods tells the Straight.

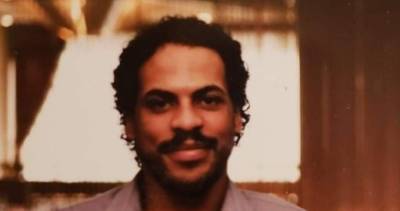

In a telephone interview, the former undercover police officer (1993-2007) and board member of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (formerly Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, an international group with members in Vancouver and across Canada), explains that as late as the 1960s, U.K. citizens addicted to opioids did not obtain the drug from a dealer, but from a doctor.

Called the "British System", the country's medicalization of opioids distribution meant there was simply no need for a black market, and therefore no petty crime that comes with an industry that exists outside of the law.

"Britain was very late to come to the prohibition table," Woods says. "It resisted the United States-driven moral imperialism for a long time. The system in the U.K. was, if you had a problem with drugs, you got help.

"With heroin, that meant a doctor would prescribe heroin to you," he continues. "Which meant that, during the time of the British System, which went from the 1920s all the way to the end of the 1960s, there was no criminal association with drugs whatsoever.

"Nobody died, because the drug that was given to people was of a pharmaceutical grade," Woods adds. "Addiction was seen as an unfortunate medical condition rather than a moral failing."

North Americans tend to think of the drug war as a U.S. phenomenon, perhaps with the occasional mention of cartel violence in Mexico and the fentanyl crisis in Canada. But prohibition is a global conflict that has left no corner of the world unscathed. In Woods's highly readable—though, at times, a little thinly sourced—account of the drug war as it has played out in the U.K., there is a lot that Canada can learn, both from Britain's successes and its many mistakes.

Woods describes how the war on drugs perpetuates itself, creating a never-ending cycle of addiction, persecution, corruption, and more addiction.

"As soon as heroin was given to the black market, then it became an incentivized product," he notes. "There was pressure from organized crime to use the dealers to find new customers. You can either pay for a problematic addiction by stealing or allowing yourself to be sexually exploited. Or you can find new customers to pay for your own habit."

Meanwhile, authorities' efforts to break that cycle created a series of unintended consequences—unintended, but not totally unanticipated.

"The arrival of fentanyl in heroin, it was predictable," Woods says. "This is called the 'Iron Law of Prohibition'. That any product in a black market will always get stronger. Just like with alcohol. Within two weeks of alcohol prohibition [in the 1930s], no one could buy beer. They could only buy moonshine or whiskey, because those are cost-effective to smuggle. This is why fentanyl is coming in: because it is cost-effective to smuggle."

These are problems born of nothing less than a grotesque transfiguration of the state's enforcement of law and order, Woods argues.

"Drug policing is qualitatively different from other forms of modern police work," he writes in Drug Wars. "Aggressively policing actions that aren’t wrong in themselves, but only wrong because they are prohibited, places very particular strains on the Peelian bond between the police and the community."

Once upon a time, policing mostly consisted of chasing burglars and responding to disputes that had turned violent. Officers were members of the communities they patrolled and maintained healthy relationships with the people they served to protect. Then drugs were declared illegal. The money followed.

"The enormous amount of money that they [criminal organizations] get from drug sales forms the bank for every other form of organized criminality," Woods says. "It has completely changed the face of crime. But, perhaps more importantly, it has completely changed the nature of policing. Because it has ended, in so many places, what should be the relationship between police and community."

The most alarming sections of Woods's book are not about drugs themselves, but about the once-unimaginable levels of corruption that the prohibition of narcotics has made possible.

"In the old days, informants were an incredibly useful tool," one of Woods's sources, another former police officer, tells him in the book. "The drug money has changed all that—to the point where a lot of criminals are now becoming informants specifically in order to manipulate the police. Having a corrupt officer in their pocket has become just another tool for any serious gangster.

"Eventually, it got to the stage with me where so many of the top echelons of any OCG [Organized Crime Group] were all registered informants, that it became impossible to properly investigate anyone—because they all have their own high-level cops protecting them.

"So, for any real detective trying to investigate organised crime, you don’t know which criminal is under the protection of which of your bosses. Suddenly your investigation is getting sabotaged from above, because you’re poking your nose into areas that might threaten someone else’s informant.

"This means you can’t actually solve cases—and if you push too hard it will harm your own career advancement," the former cop laments. "So any talented, ambitious detective looking at the drug trade is now hobbled from the start."

Woods tells the Straight that after 14 years as a police officer who waged the drug war and then a subsequent decade spent fighting against it, he's come to view prohibition as significantly more harmful than the general public understands.

"We're sleepwalking, not realizing just how horrific is the situation that's been created," Woods says.

Comments